For decades, Utilities were the textbook defensive sector: regulated earnings, predictable cash flows and slow but stable investment cycles.

They were not exciting.

They were dependable.

AI is now putting that identity under pressure.

Unlike previous technology waves, AI is not just software. It is physical infrastructure: data centres, electricity grids, generation assets and new capacity built years ahead of revenue certainty.

Utilities are at the centre of this build-out.

Recent hedge-fund positioning reflects this shift. According to Goldman Sachs, Utilities are now the most shorted sector in the S&P 500 (as a percentage of market capitalisation), a sharp departure from historical norms.

The Financial Times summarised it bluntly:

“Normally boring utility stocks have begun to look a little racy.”

At Sismo, we examined this through a capital-allocation lens.

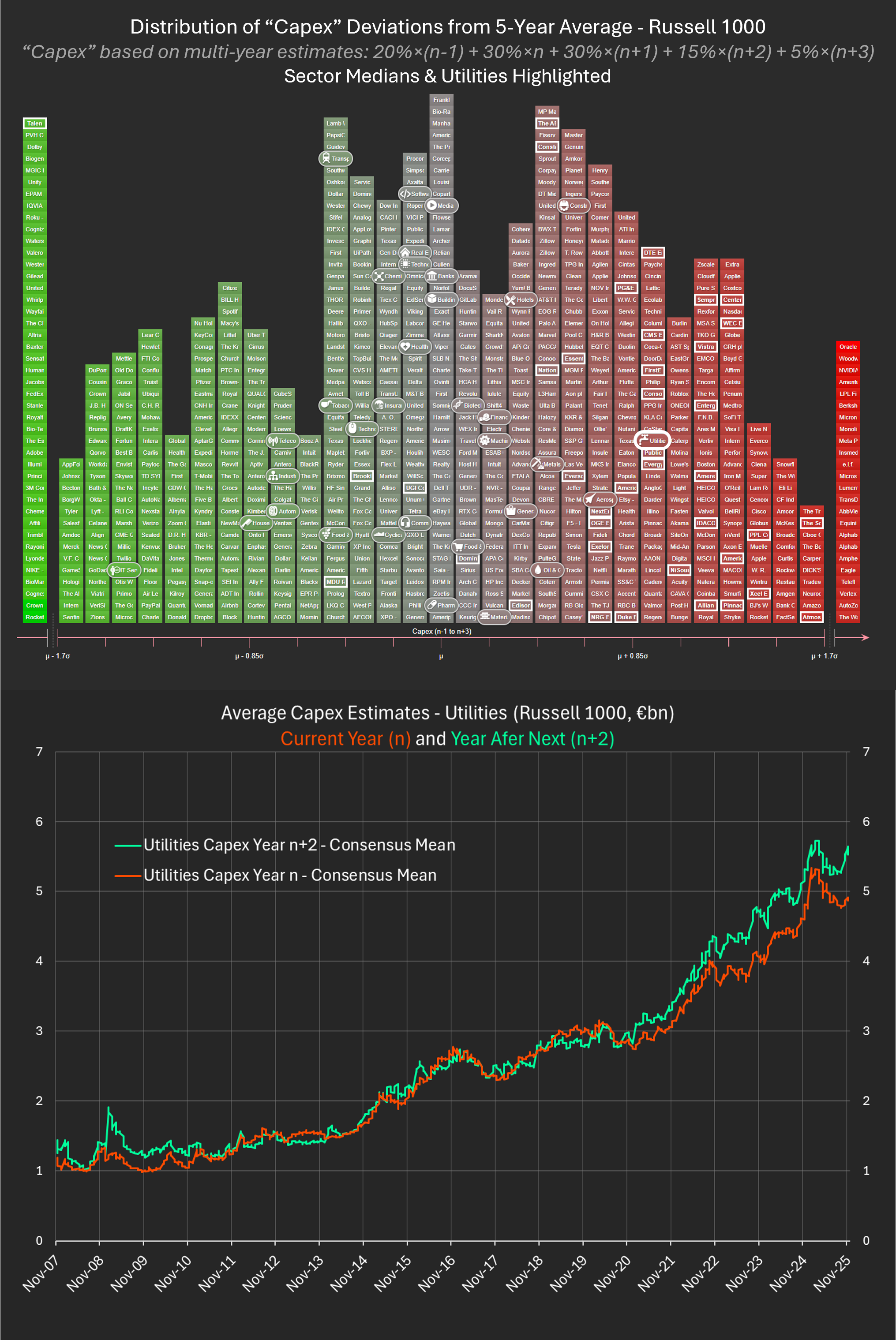

Rather than focusing on prices or valuations, we constructed a composite Capex indicator using the latest reported year and forward analyst estimates (from FY-1 through FY+3), designed to capture both near-term intensity and medium-term commitment.

We then measured each company’s current investment level versus its own five-year history using a History-Z methodology - expressing today’s capex relative to past regimes.

This removes cross-sector and size distortions and isolates true behavioural change.

The results are unambiguous.

Across the Russell 1000, Utilities display the most extreme positive deviation from historical investment norms of any sector. Median positioning stands more than 1.2 standard deviations above the five-year average - well beyond what is typically observed for stable, regulated industries.

The time series reinforces the picture.

From 2007 to 2020, utilities’ capex rose gradually.

From 2021 onward, it inflects.

From late 2022, it accelerates sharply.

Forward estimates steepen at the same time.

The inflection point coincides with the industrialisation of generative AI.

This does not imply that Utilities are mis-allocating capital.

But it does raise a fundamental investment question:

Who carries the risk if infrastructure is built faster than revenues materialise?

If AI demand unfolds as projected, Utilities may evolve into strategic growth infrastructure - no longer defensive, but essential.

If demand disappoints, pricing weakens, or energy efficiency improves faster than expected, Utilities could be left with front-loaded investment, long amortisation cycles and returns built on assumptions that no longer hold.

This is not a call on AI.

It is a call to recognise that capital risk has moved.

AI is not just transforming technology stocks.

It is reshaping balance sheets - and risk profiles - in the power system itself.

Utilities may be one of the clearest early examples of that shift.

.jpg)